Discuss this article on the forums

“The failure to agree on firm diagnostic criteria has distorted the data base for epidemiological and other research, thus denying recognition of the unique epidemiological pattern of myalgic encephalomyelitis.”Dr. Melvin Ramsey

“The Month Of ME’ – in response to a challenge and in recognition of the important role the term myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) has played and continues to play in this disorder, August, 2011 will be the ‘Month of ME’ on Phoenix Rising. We examine ME’s role in this disorder throughout the month. All articles, blogs and posts produced by Phoenix Rising only used the term myalgic encephalomyelitis or ‘ME’ unless ME/CFS or CFS was absolutely required..In reward for doing so, GregF, a Forum member, contributed $1,000 to the Whittemore Peterson Institute. Although it was not in the bargain he also generously contributed $320 to Phoenix Rising.

Defining either ME or CFS has never been easy. Both disorders effect multiple systems of the body, can cause a wide variety of symptoms and are difficult to treat. Decades of intermittent study in CFS has not lead to a clear understanding of the disorder. Many researchers believe the problem tracking down the cause of CFS is not the ‘disorder’ per se – but the definition itself.

The Fukuda definition that has, since 1994, dominated the field, has done part of it’s job – multiple problems have, after all been documented in people with CFS – but the pace has been slow and ragged. A tighter definition that ties a closer knot around ‘CFS’ could accelerate the field. That, of course, is where myalgic encephalomyelitis comes in.

ME, which started out as a disorder associated with infectious outbreaks, has always been more exclusive than CFS but ME has had a difficult path. Lacking a definition backed by extensive research or strong backing from the research community, ME’ research, always rare anyway, disappeared from the research scene when a team lead by the powerful CDC coined the term ‘chronic fatigue syndrome’ and provided their definition. Now ‘CFS’ was in, and ‘ME’ – which had gotten into the WHO classifications – but which had failed to gain significant research support – was completely out.

Twenty plus years later the publication of the International Consensus Criteria for Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ICC) in a major journal re-introduced the term ‘ME’ to the larger research community and created a new definition for myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME).

The most comprehensive definition to date, the ICC is only the latest of a stream of definitions. The term myalgic encephalomyelitis was coined in a 1956 Lancet publication by Dr. Ramsey and then endorsed in a large review article by Acheson titled “The clinical syndrome variously called benign myalgic encephalomyelitis, Iceland disease and epidemic neur?myasthaenia” (PDF). It took several decades, however, before formal definitions were produced. Like the definitions for CFS the definitions for ME have changed over time.

It took several decades, however, before formal definitions were produced. Like the many definitions for CFS the definitions for ME changed over time. In this article we take a look at the different conceptions of ME over time. We start off with ME’s most dedicated proponent, Dr. Melvin Ramsey.

Dr. Melvin Ramsay

Dr. Melvin Ramsay was a UK doctor involved in the Royal Free ME outbreak. Over the next 30 years Ramsey became ME’s most ardent advocate writing at one point a 68 page book (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Postviral Fatigue States: the Saga of Royal Free Disease”) and producing several of the earlier definitions.

Dr. Melvin Ramsay was a UK doctor involved in the Royal Free ME outbreak. Over the next 30 years Ramsey became ME’s most ardent advocate writing at one point a 68 page book (Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Postviral Fatigue States: the Saga of Royal Free Disease”) and producing several of the earlier definitions.

Ramsay had an acute eye. In 1986 at about the same time Dr. Peterson, Cheney and Bell were fighting outbreaks in the US, Ramsey, after more than 30 years of experience with the illness was writing that ME usually occurred after a upper respiratory cold, was characterized by severe fatigue and such symptoms as ‘attacks of giddiness (dizziness), urinary frequency, headaches, muscle weakness, neck pain, double vision, low body temperatures, difficulty concentrating, emotional lability and just ‘feeling awful’. Interestingly given the recent focus on the peripheral nerve ganglia by the Lights and Shapiro the first possible viral factor he mentions is varicella-zoster (herpes simplex) infection in the nerve ganglia. Ramsey was ahead of his time when he suggested that the triggering virus may not be as important as an aberrant immune response.

The First Definition – RAMSAY 1986 – A Hallmark Symptom Highlighted (https://www.name-us.org/DefintionsPages/DefRamsay.htm)

Ramsay’s 1986 definition not surprisingly was a definition of firsts. He termed the disorder a syndrome – a condition whose cause was unknown – usually triggered by a viral infection but ( a first) which could have an ‘insiduous’ (stealthy) onset triggered by some neurological, cardiac or endocrine disability. Like the recent International Consensus Criteria Ramsey proposed that ME is primarily a neurological disorder with significant multi-systemic problems.

In contrast to the outbreak literature which focused on neurological symptoms, in particular, localized muscle weakness/paralysis, Ramsey’s top three symptoms were headaches, malaise (fatigue) and interestingly enough, dizziness (orthostatic intolerance). Other major symptoms were swollen lymph nodes and an unusual one,‘ rash’. (Rash was not noted in Acheson’s 1959 report on the outbreaks, or later in the International Consensus Definition (ICC) in 2011 or in the Fukuda definition of CFS.

Ramsay’s called the disorder a ‘unpredictable state of central nervous system exhaustion’ using a phrase (nervous system exhaustion’) often used in the past to describe neurasthenia but which also hearkened forward to the ICC’s ‘Post exertional neuro-immune exhaustion’ (PENE). Ramsey was the first to codify the strange response to exertion in a definition noting that the central nervous exhaustion in the disorder typically followed mental or physical exertion.

In his works Ramsay again and again focused on the problems of ‘fatigue’ and exertion stating in 1986 that the ‘dominant clinical feature’ is ‘profound fatigue’ and that those patients who in the attempt to ‘snap out of it..take plenty of exercise’ find themselves in a ‘state of constant exhaustion’. He noted that ‘any excessive physical or mental exercise is likely to precipitate a relapse’. https://www.name-us.org/DefintionsPages/DefRamsay.htm

Ramsay/Dorsett 1990 – A Step Forward (and A Step Backward?)

‘

By 1990 Ramsay’s definition (Ramsay/Dorsett) had undergone some changes. The possibility of gradual onset was more clearly recognized and the focus was on muscle fatigue, not just fatigue. The prolonged recovery times after minimal exertion was more clearly delineated and portrayed as a key finding. ME was viewed as a neurological disturbances with problems with a strong cardiac focus.

In some ways, though, the 1990 definition seemed to be something of a step backwards. In 1988 neurological disturbances and the relapsing nature of the disorder were strongly linked to too much exertion but not in the 1990 definition.

Just four years later a new and more comprehensive definition would make its way into a research journal and this one would put ‘exertion based problems’ front and center.

LONDON CRITERIA FOR M.E. – An Exertion Based Disorder Takes Center Stage

LONDON CRITERIA FOR M.E. – An Exertion Based Disorder Takes Center Stage

Dowsett EG, et al. London criteria for M.E. In: Report from The National Task Force on Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS), Post Viral Fatigue Syndrome (PVFS), Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME). Westcare, 1994. pp. 96-98.

The London Criteria for ME just four years later in 1994, set a new standard for comprehensiveness with its long list of symptoms and exclusionary criteria. Ramsey had emphasized the negative effects of too much exertion in his definition but the London Criteria put them front and center for the first time – demonstrating an insight that has eluded the authors of CFS definitions (Fukuda, Oxford, Empirical) and their focus of fatigue for years.

The London definition required that three things be present – high levels of exertion induced fatigue, problems thinking/concentrating and a relapsing/remitting nature of the symptoms usually provoked by exertion.

It proposed that all ME patients must exhibit ‘exercise induced fatigue induced by trivially small physical or mental exertion’ relative to their former levels and asserted that the relapse/remitting phase of ME was often tied to the degree of physical or mental exertion undertaken.

(Note that the definition is relative; the degree of incapacity relative to former activity levels is key – not the level of debility. Thus, an athlete could have ME if she/he was forced to cut back on athletic activities greatly even if his/her rate of exercise was still higher than normal.)

The London authors also asserted for the first time that thinking problems were not just there but were hallmark features of the disorder as well. The authors agreed with Ramsey/Dorsett that a viral onset was predominant but they fleshed out the gradual onset aspect of ME more stating that ‘in a minority of patients, M.E./PVFS has a gradual onset with: no apparent triggering factor” which could involve immunizations, traumas and chemical exposure. As if to make sure their point was taken they also stated that “For these reasons proof of a preceding viral illness is not a prerequisite for diagnosis”.

The London definition tried to get a different kind of patient into ‘ME’ (or as they also called it ‘post-viral fatigue syndrome’) studies. For the first time they presented a long list of disorders that could be confused with ME and asserted that patients with anhedonia (inability to experience pleasure), feelings of worthlessness and guilt, apathy, etc. should be screened for major depression and ‘if there is any doubt whatsoever’ as to their diagnosis should be excluded from ME research studies. Unfortunately the research community continued to focus on CFS (Fukuda definition) defined disorders and few or no ‘ME’ oriented studies resulted.

The London definition also a long list of symptoms characteristic of the disorder; it was the first definition to note the “ curious intolerance to alcohol and hypersensitivity to drugs” that was present or that a positive Rhomberg test generally occurred.

Next came an influential and at times controversial figure, Dr. Byron Hyde, who – heavily steeped in the outbreak literature and his own experience treating the disorder – came to view ME in a different light indeed.

The Hyde Divide – ME and CFS

The Hyde Divide – ME and CFS

An ME physician with decades of experience treating ME Hyde has played a large role in the definition debate, writing important chapters in two key texts on diagnosis including ‘The Basics of Diagnosis’ in the 2003 “Manual on CFS” and following that up with his own book “Missed Diagnoses; Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome’ in 2010. His 2007 definition with commentary and citations ran 19 pages and was followed up by a shorter definition in 2010.

Hyde’s vision of ME has been deeply grounded in the outbreaks and his personal experience treating the disorder. Like the authors of the London Definition Hyde appears to have been deeply disturbed by the negative impacts he thought the broader definitions of chronic fatigue syndrome had had on the research leading him again and again to attempt to differentiate ME from CFS. In Hyde’s definition mentions of fatigue were anathema and the focus on exertion was blunted.

In the 2003 chapter “The Complexities of Diagnosis” Hyde produced 8 factors he felt differentiated ME from CFS and then four essential differences, the most important of which is type of onset.

Eight Factors That Differentiate ME from CFS

- The epidemic characteristics

- The known incubation period

- The acute onset

- The associated organ pathology, particularly cardiac.

- Infrequent deaths with pathological CNS changes.

- Neurological signs in the acute and sometimes chronic phases.

- The specific involvement of the autonomic nervous system.

- The frequent subnormal patient temperature.

- The fact that chronic fatigue is not an essential characteristic of the chronic phase of ME.

The Key Differentiating Factor

Gradual Onset! – Hyde felt the key differentiating factor between the two, though, was type of onset and that including gradual onset patients in ME (ie CFS) was a major mistake. Hyde stated in strong terms that

Hyde felt that many of the gradual onset patients ‘simply’ had an undiagnosed medical condition that was causing their symptoms.

This condition, not surprisingly given their generally extensive medical write-ups, was often not easy to find. Hyde that had taken him several decades to be able to consistently correctly diagnose the gradual onset patients and he described, in ‘The Complexity of Diagnosis (attached) the exhaustive laboratory examination process he uses (called ‘total body Mapping’) to uncover missed problems. (Hyde does not believe ME has one cause either. Viral agents, for instance, he believes only cause about 10% of ME cases and he eschews many of the viral tests other ME practitioners use. Hyde’s 2010 book “Missed Diagnoses: Myalgic Encephalomyelitis and Chronic Fatigue Syndrome” describes his examination process in detail).

Hyde did not downplay the serious problems people with gradual onset have stating that “The gradual onset CFS group is of particular concern to me. It is in this group that occult disease, whether malignant, space occupying, organ pathology, or vascular injury of the CNS or cardiac system, is most frequently observed.” Terms are clearly getting a bit confused as earlier Hyde had stated that organ pathology was something that differentiated people with ME from people with CFS (people with CFS had none) and he will go on to highlight vascular injury in the CNS in ME cases.

Surely Hyde has a point – one would think more misdiagnoses would occur in gradual onset patients yet his insistence that poor diagnostic abilities lead to the inclusion of a major subset of patients who had another disease into ‘ME’ or ‘CFS’ must have rubbed many of his fellow physicians wrong. (Hyde presented several sample cases he successfully resolved who had visited well known ME/CFS clinics in the US. )

None of the major ME physicians such as Cheney, Bateman, Bell, Klimas, etc. nor even Peterson with his immune focused subset, etc. have stated that gradual onset patients are not part of ‘ME’.

Hyde’s Definition of ME

We’ve taken a brief look at how Hyde differentiates ME from CFS. Now we look at Hyde’s most recent definition of ME. Looking back apparently on 60 or so reports of outbreaks over the last 80 years Hyde reported that ME generally has an incubation period of 4 to 7 days.

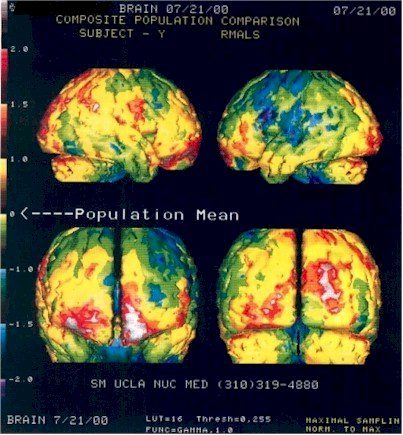

A Key Test -The SPECT SCAN – Hyde ploughed new ground when he argued that laboratory tests measuring central nervous system functioning can diagnose ME. These laboratory tests – SPECT scans, in particular, but also PET and EEG scans – reveal, he believes, a ‘diffuse’ central nervous system dysfunction that plays a central role in ME. Hyde’s definition states

The SPECT scan, though, which measures blood flows in the brain, is the make or break test with ME. Hyde stated in ‘The Complexity of Diagnosis’ that

Hyde noted in some detail the kinds of SPECT findings ME patients should have; decreased perfusion of blood in the left middle cerebral artery and the branches of the parietal lobes, etc. and these were present very early in the illness.

The type of EEG (electrical activity of the brain) or PET (metabolic) abnormalities typically found in ME are not clarified – rendering those criteria less useful for defining ME.

The SPECT scan data is the central filter Hyde uses. No other required abnormalities are present but Hyde notes that ME patients also tend to have a long list of other problems which are listed below; essentially as a group people with ME tend to difficulty concentrating and finding words, etc, problems sleeping, poor muscle functioning, trouble standing without exaggerated heart rates and dizziness, little ability to exert themselves, cold fingers, loose joints and gut problems. Hyde also puts a strong focus on thyroid abnormalities – a new addition to the ME pantheon. (In ‘Missed Diagnoses Hyde states that about 17% percent of his ME patients have thyroid cancer.)

The SPECT scan data is the central filter Hyde uses. No other required abnormalities are present but Hyde notes that ME patients also tend to have a long list of other problems which are listed below; essentially as a group people with ME tend to difficulty concentrating and finding words, etc, problems sleeping, poor muscle functioning, trouble standing without exaggerated heart rates and dizziness, little ability to exert themselves, cold fingers, loose joints and gut problems. Hyde also puts a strong focus on thyroid abnormalities – a new addition to the ME pantheon. (In ‘Missed Diagnoses Hyde states that about 17% percent of his ME patients have thyroid cancer.)

(Hyde’s list of testable abnormalities includes neuropsychological abnormalities (described in detail in his long definition https://www.nightingale.ca/documents/Nightingale_ME_Definition_en.pdf), major sleep dysfunction, muscle dysfunction (tests not clarified), vascular and cardiac dysfunction (eg POTS, heart/pump volume rate in response to exertion, Raynaud’s phenomenom, low blood volume, Ehlors-Danlos Syndrome, bowel dysfunction, clotting defects, anti-smooth antibodies and unspecifiec antibodies.)

Interestingly, except for the anti-smooth antibodies Hyde never notes any of the immune findings such as natural killer cell dysfunction, RNase L dysfunction and cytokine abnormalities that other doctors use to guide their treatment plans. Nor is there any mention of pathogens. Herpesviruses, which absorbed more physician and researcher attention than any other pathogens until XMRV came along, are not mentioned. In contrast to Peterson, Lerner and Montoya’s focus on herpesviruses Hyde later states the he believes enteroviruses are a major factor in ME/CFS but are simply difficult to find. Dr. Peterson or Dr. Lerner’s or Dr. Klimas’s definition of ME would probably have both significant similarities and significant differences.)

Hyde’s ME and the ICC’s ME: Different Aims – Different Definitions

Hyde’s definition of ME with it’s focus on lab tests, has a clarity that the ICC definition with its rather complex list of symptoms can not. The ICC, however, is attempting to achieve a different goal than Dr. Hyde- a goal which presented significant restrictions Dr. Hyde did not operate under.

Hyde’s longstanding personal experience as a physician with ME allowed him to highlight abnormal lab tests he consistently found in his ‘ME’ patients. Hyde’s focus on his personal findings gave him the potential to inject new elements into an ME definition but the scientific communities focus on studies rather than anecdotal reports means that Hyde’s impact will be blunted there (until he publishes in peer reviewed journals. In ‘Missed Diagnoses’ (2010) he reports that some are underway). Hyde’s main effect, then, has been to inform and provoke and open up new vistas for the disorders for physicians – something he makes plain in his long definition.

The ICC attempt to reintroduce ME as a mainstream disorder into general scientific thought required that they rely on study evidence to present their case. (The study results for SPECT, EEG and PET scan in CFS is mixed and in any case was done on ‘CFS’ patients. That may very well be because both ‘CFS’ and ‘ME’ patients were present in the studies but that remains to be proven.

The ICC co-authors are in something of a catch-22 position. Since no studies on the ICC’s ‘ME’ have taken place the best they can do is to point to tests on ‘CFS’ patients and say we think these abnormalities will be characteristic for ME. (Hyde has the same problem of course -virtually all the abnormalities he refers to in his longer definitions come right out of CFS studies). Nobody will actually know what abnormalities are present in ‘ME’ until studies actually start using the ICC definition. The hope, of course, is that once more tightly defined patients are placed in studies, strong, consistent physiological abnormalities will be found that lead researcher to the core problems in the disorder.

A Different Hallmark Dysfunction – In contrast to the ICC’s hallmark symptom ‘post exertional neuroimmune exhaustion’ or PENE, Hyde believes vascular problems are “the most obvious dysfunction(s) in ME when looked for and probably (are) the cause behind a significant number of the …complaints” and these are best uncovered using SPECT scans of the brain.

A Different Hallmark Dysfunction – In contrast to the ICC’s hallmark symptom ‘post exertional neuroimmune exhaustion’ or PENE, Hyde believes vascular problems are “the most obvious dysfunction(s) in ME when looked for and probably (are) the cause behind a significant number of the …complaints” and these are best uncovered using SPECT scans of the brain.

Hyde certainly understands the negative effects of exertion on ME patients – but has expressed strong reservations about using exertion based fatigue or symptom exacerbation as a hallmark feature of ME in part because of the difficulty measuring them. Hyde strong aversion to ‘fatigue’, however, has lead him to make some statements that appear questionable in the light of the historical evidence.

De-Emphasisng Fatigue and Exertion Based Problems – In his 2007 definition Hyde stated that ‘fatigue was never a major diagnostic criteria of ME’ and that ‘loss of stamina, failure to recover quickly occur…in most if not all progressive terminal diseases and in a very large number of chronic non-progressive or slowly progressive diseases” thus making that a poor diagnostic tool for ME. Hyde stated “Fatigue and loss of stamina…cannot be seriously measured…and do not assist us with the diagnosis of ME or CFS or for that matter any disease process”

In the ‘Complexities of Diagnosis’ chapter Hyde presented a more nuanced view of the fatigue/exertion issue in ME stating that ‘overwhelming fatigue is often a feature of the chronic illness phase” and that it changes over time from mere fatigue to an exertion related phenomena.

There may be no better description of the fatigue/exertion dilemma in CFS literature but later on Hyde states that “that chronic fatigue is not an essential characteristic of the chronic phase of ME.” Hyde appears to be pointing out the role that exertion plays in producing fatigue in ME as opposed to an always present fatigue that may be present in CFS.

‘A Profound and Unusual’ Exhaustion’ – Hydes statement, however, that “chronic fatigue is not an essential characteristic of the chronic phase of ME” is questionable as many authors have remarked on it. In the Coventry outbreak the authors reported that ‘extreme fatigue… made the rehabilitation period extremely tedious and long’. Seven to ten months after the Akureyri outbreak ‘nervousness, fatigue and persistent muscle pains were common. Two years afterwards Deischer reported the most common problems were ‘tiring easily’ followed by pain and stiffness.

In Dr. Ramsey’s and Dorsett’s 1977 letter to the British Medical Journal on ME they stated that the most characteristic presentation is profound fatigue…increasing in severity with exercise. A letter to the BMJ on epidemic myalgic encephalomyelitis on June 3rd ,1978 states ‘One characteristic feature of the disease is exhaustion, any effort producing generalized fatigue”. In Dr. Acheson’s summary he states that ‘in some instances a characteristic syndrome of chronic ill health has developed with cyclical redrudescences of pain, fatigue, weakness and depression…”

In the more modern era the first symptom that Dr. Ryll, a U.S. physician who conducted one of the longest continual study of ME patients on record (1975-1994), listed was severe exhaustion. He noted that the ‘exhaustion that occurs in this disease is profound and unusual”. Drs. Cheney, Komaroff, Peterson, Buchwald, etc. required that patients experience ‘chronic debilitating fatigue’ for at least 3 months in order to participate in the study and Dr. Ramsey in 1986 twice referred to the ‘dominant clinical feature of profound fatigue’ in ME. The Ramsey and Dorsett ME criteria (1990) stated that the first cardinal feature of ME is ‘generalized or localized muscle fatigue after minimal exertion with prolonged recovery time’.

Hyde’s focus away from a symptom based disorder focusing on fatigue or exertion -a difficult factor to measure – to one diagnosed by laboratory testing – particularly SPECT scans – was understandable. Defining ME in such a way that laboratory abnormalities become more and more evident, of course, has been probably the prime hope of all ME definition authors since the Ramsay/Dowsett definition in 1986.

Disease Course – Hyde also used his personal experience (and historical reports) to chart new ground with his emphasis on ‘disease course’ in his definition. According to Hyde ME has firm incubation period, a specific time at which CNS abnormalities show up in testing (very quickly), has endocrine abnormalities that tend to come on later in the disorder, pain levels that to tend to decline over time , cognitive problems that do the same (given the right social and financial support) and muscle weakness generally improves. None of these trends are mentioned in the ICC or other definitions.

Conclusions

The 1986 Ramsay, 1990 Ramsey/Dorsett and 1994 London Criteria can be seen as increasingly complex iterations of the same basic definition with the London Criteria achieving a kind of comprehensiveness lacking in the others. All the definitions described ME as primarily a neurological disorder and none asserted a certain pathogen or type of pathogen was key to ME.

Hyde’s work suggests he was looking at the same type of patients but his definition took a sharp turn. In contrast to the other definitions Hyde asserted that gradual onset patients did not have ME but were generally suffering from other undiagnosed disorders. While acknowledging the presence of exertion-based fatigue in his patients, Hyde eschewed those factors as fundamental both in a historical sense and a pragmatic one instead focusing on central nervous system tests he had personally found were diagnostic for the disorder. Hyde also for the first time Hyde also described a general disease process in ME.

The ICC also describes ME as a neurological disorder but it’s mission – to use study evidence to convince the research community that ME is a legitimate disorder existing apart from chronic fatigue syndrome – made it impossible for the ICC to take Hyde’s approach or use Hyde’s evidence. In a sense Hyde has what the ICC wants – documented evidence of a central abnormality in ME that distinguishes it from other disorders – but not in the form it needs (study evidence). If the research community begins to test the ICC’s assumption – that ME is a different disorder from CFS – that evidence will hopefully emerge over time. The key task for the co-authors of the ICC is to convince the research community and funders that their definition is worth testing.

APPENDIX – The Definitions (see attachments for London and Hyde Definitions)

Ramsay’s 1986 Definition https://www.name-us.org/DefintionsPages/DefRamsay.htm

“A syndrome initiated by a virus infection, commonly in the form of a respiratory or gastrointestinal illness with significant headache, malaise and dizziness sometimes accompanied by lymphadenopathy or rash. Insidious or more dramatic onsets following neurological, cardiac or endocrine disability are also recognised. Characteristic features include:

- A multisystem disease, primarily neurological with variable involvement of liver, cardiac and skeletal muscle, lymphoid and endocrine organs.

- Neurological disturbance – an unpredictable state of central nervous system exhaustion following mental or physical exertion which may be delayed and require several days for recovery; an unique neuro-endocrine profile which differs from depression in that the hypothalamic/pituitary/adrenal response to stress is deficient; dysfunction of the autonomic and sensory nervous systems; cognitive problems.

- Musco-skeletal dysfunction in a proportion of patients (related to sensory disturbance or to the late metabolic and auto immune effects of infection)

- A characteristically chronic relapsing course.”

Ramsay/Dowsett 1990 https://www.name-us.org/DefintionsPages/DefRamsay.htm

A syndrome initiated by a viral infection commonly described as a respiratory/gastro intestinal illness but a gradual or more dramatic onset following neurological, cardiac or endocrine disability is recognised.

The cardinal features, in a patient who has previously been physically and mentally fit, with a good work record are:

- Generalised or localised muscle fatigue after minimal exertion with prolonged recovery time.

- Neurological disturbance, especially of cognitive, autonomic and sensory functions, often accompanied by marked emotional lability and sleep reversal.

- Variable involvement of cardiac and other bodily systems.

- An extended relapsing course with a tendency to chronicity.

- Marked variability of symptoms both within and between episodes.”