Epstein-Barr Virus (or EBV) was the first major disappointment for CFS researchers. Several studies in late eighties suggested EBV might be the cause of CFS but subsequent studies revealed EBV activation to be no higher in CFS than controls. In recent years, however, like Lazarus rising from the grave, EBV’s role in CFS has been given new life by several research groups that have continued to examined this intriguing virus in greater detail.

Historical Background

EBV has a long history in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS). The finding of increased antibody levels to EBV in 1985 suggested that a chronic EBV infection caused ME/CFS. Five studies between 1985 and 1988 indicating ME/ CFS patients had increased levels of antibodies to EBV lead to the disease for a time being ca lled Chronic Epstein-Barr Virus (and the CFIDS Association of America being called the Chronic Epstein-Barr Virus Association).

Further studies, however, found that healthy people often had similar antibody levels and later studies found no evidence of unusual EBV reactivation in ME/ CFS.

The inability of researchers to find EBV DNA in the throat washings of CFS patients – a common finding in immunosuppressed subjects – suggested ME/ CFS patients were not subject to high levels of EBV reactivation. Importantly no studies were able to link antibody levels or viral load to symptom severity in the disease and interest in EBV as a causative agent waned.

Two research groups have maintained interest in EBV, however, and the recent CDC sponsored Dubbo studies have once again brought it to the fore. There are at least three ideas regarding EBV and ME/ CFS:

- Rates of active EBV infection are not higher in chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) patients than the population at large: EBV infection does not play a role in this disease.

- EBV infection during adolescence/adulthood that leads to infectious mononucleosis is a risk factor for ME/ CFS.

- An ongoing chronic and mostly undetected EBV infection by itself or in interaction with other viruses causes significant symptoms in a subset of patients.

Background

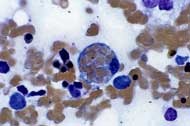

The presence of Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) in our saliva makes EBV infection common. Indeed EBV, or as it is now called human herpesvirus 4 (HHV-4), infection is almost ubiquitous. EBV, which was discovered in 1964, resides in resting (memory) B-cells, usually for life. Early in the infection EBV turns on genes that produce new viruses (virions) that go on to infect new cells. By the time the immune sytem knocks EBV it has usually established itself in the DNA of B-cells.

Except for occasional forays at reactivation to reestablish itself in new cells once EBV establishes itself in B-cells it turns its activity levels down enough to run under the immune system’s radar. Everytime the B-cell duplicates, though, the presence of EBV DNA in the cells DNA allows the virus to be duplicated as well. EBV, then, does not need to infect new cells to remain present in the body for life.

Most people carry a fair constant number of EBV infected cells in their bodies. The number of infected cells each person carries can vary enormously, however. People with higher levels of EBV infected cells are not necessarily less healthy than people with lower levels of cells.

Primary EBV infection

The consequences of an EBV infection vary dramatically depending on when it occurs. While a primary (initial) infection during childhood is usually benign, a primary EBV infection during adolescence causes infectious mononucleosis in about 30-40 percent of those infected, and about 10% of those infected come adown with a post-infectious fatigue syndrome or CFS. A recent study found that those that encountered EBV later in life – i.e. came down with infectious mononucleosis – had a higher risk of coming down with MS than those exposed to it as a child.

EBV, then, is not as benign as was once thought. Sooner or later most people get exposed to EBV. If you do so as a child you usually have a mild infection, if you do so as an adolescent or adult you have a good chance of getting infectious mononucleosis, and if you get infectious mononucleosis you have a fairly good chance of coming down with post-viral fatigue or chronic fatigue syndrome, and an increased (but still low) chance of getting MS.

EBV, then, is not as benign as was once thought. Sooner or later most people get exposed to EBV. If you do so as a child you usually have a mild infection, if you do so as an adolescent or adult you have a good chance of getting infectious mononucleosis, and if you get infectious mononucleosis you have a fairly good chance of coming down with post-viral fatigue or chronic fatigue syndrome, and an increased (but still low) chance of getting MS.

EBV reactivation

A recent paper suggests that the old paradigm; irregular attempts by EBV to reactivate and infect new cells is wrong. This paper suggests that EBV is constantly testing the immune system. This occurs when EBV infected B-cells move into the lymphoid organs (e.g. lymph nodes, spleen) where they get triggered by antigens (pathogenic particles) to transform themselves into plasma cells and produce antibodies. During this transformation EBV uses the B- cells genetic machinery to produce more EBV virions. This reactivation process is kept in check by EBV spectific cytotoxic T-cells.

The vast majority of EBV reactivation cases are benign, however, and go unnoticed. Some degree of EBV reactivation is normal and expected in everyone carrying the virus. One study found that EBV reactivation was present in about 10% of healthy individuals. Another found a detectable viral load was present in over a third of healthy individuals and another that about 25% of healthy individuals had EBV DNA in their blood (Maurmann et. al. 2003).

EBV reactivation is, however, implicated in several very rare cancers and may be associated with transplant rejection and multiple sclerosis. Several situations, including an impaired innate immune response, physical or psychological stress, organ transplantation and HHV-6 and HIV infection have been shown to trigger the EBV reactivation.